!["That Joke Has Everything": David Letterman, Before Late Night]()

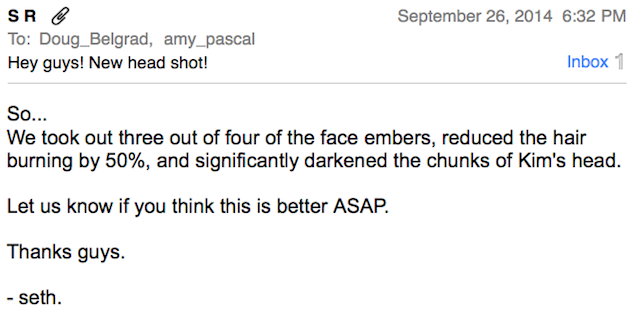

In December 1981, a month before Late Night With David Letterman debuted on NBC,

Peter W. Kaplan profiled the young comedian, and heir-apparent to Johnny Carson, for Esquire. The story is reprinted here with permission.

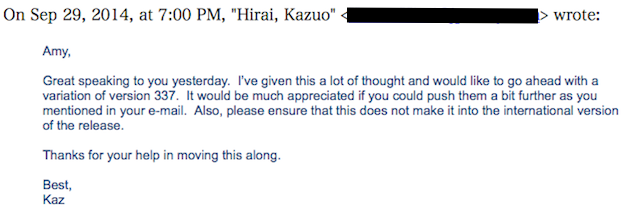

When David Letterman enters a small club, other young comics make way for him, and although he moves among them, he is separate. They haven't hosted

The Tonight Show and he has. The other young comics have to beg audiences for their attention at lonelier clubs, on later nights, attacking them, splaying their personalities onstage. They do imitations of Bigfoot in different dialects, they imagine the Elephant Man doing ads for the Chrysler K-car, they evoke and torture their parents' domestic intimacies before a high, dark room full of people in Westwood or Santa Monica or Hollywood. Blinded by a spotlight, a young comic stands on a stage and calls jokes into the night, waiting for the laughter, hearing his own voice in its terrifying clarity—a sound garnished by a few low coughing chuckles from the crowd. "So you hate me," the young man says with sweaty anger. "What do I care? Anyone got a cigarette?" He is given one. "So you hate me… so I'll talk to my dick." He pulls his waistband and talks down into his crotch. "Hello, Poky!" he says. "How are you Poky? Jump, Poky. Please?" There's a silence, and the young man glares out into the black. "I always get best when I feel mean," he says, and resumes talking to his crotch. The audience turns its head and coughs.

No such quiet fills a room when David Letterman comes through a curtain; quiet skitters away like many fleeing waiters. People yell, "Hey-yo!" and they yell, "How hot was it!" They seem to feel very close to Letterman indeed, and he stands and laughs in his white sweater and blue jeans and swings the microphone around like the old pro he's practicing to be. "Hey-yo!" a straggler calls. "What a

fine crowd," Letterman says, and that gets the laughs it seeks. The audience is all in favor of allowing Letterman to make them laugh; they know he's funny. He just has to talk, and they work so that he'll acknowledge them. "This is more fun," Letterman tells the crowd, "than humans should be allowed to have." They laugh and clap. "Hey-yo!" someone yells.

Other young comedians come and go. They work the rooms and they yearn for their moment under the television lights—the moment that can turn them into paradigms of our age, the names cut into the marble walls of our culture halls: BRENNER. CHASE. KLEIN. Some can do dialect humor, others can simulate young people on drugs for an audience's satisfaction, others can insult their wives. None of them will do anything that really hurts because that would keep them off television and push them into selling aluminum siding (which DANGERFIELD almost had to do).

The comedian who can make it on television is the one who can preside over the talk show landscape. He's the comedian who can keep things going and react to the traffic of guests sitting down on and leaving a couch; he's the comedian who represents security and durability to a network. Who knows, who even cares anymore, whether Johnny Carson is actually funny? We know that we like to laugh with him, but who knows whether he actually pushes the catch lever that leads to the joy-pain spasm? He is, more than anything, a triumphant and reassuring habit; he can react and act with the flow of the society, and because of that he's worth more than any eight sitcoms.

David Letterman is that sort of good horse, the good choice in the morning lineup to provide thirty or forty or fifty years of solid, non-scalding comedy for national consumption. Like Carson, he knows that the long run is left to those who know to hold off and save it for the stretch. He's not the one to wing it up toward the sun or to kill the audience a thousand times and himself last. When he works an audience, Letterman works at half speed so that he can

generate while he goes; it's the broadcast tradition of the talker. He goes on and on when he works, sending tendrils out into an audience, practicing. Just a funny guy is David L., just a firm hand who keeps his hostility in check, unsheathing, like Carson, a measured fury, and this restraint is what entitles him to the right to endure in a television age. Someone's yelling "Hey-yo!" at Letterman, and because of that, all of that, NBC is paying him one million dollars a year. Letterman will inherit the air and the cables, gather his resources, and almost never reach for the emergency weapon—the lethal anger behind the sheet of glass—that the smartest ones keep in reserve for the moment of crisis when they doubt, and so need to demonstrate, that they are unchallengeably in charge of their audience.

On the ride over to the Comedy and Magic Club in Hermosa Beach, Calif., Letterman leans his head back on the front seat of his friend Tom Dreesen's Chevy and looks through the windshield of tinted glass at the black California sky. He has a cold and can't breathe very well, but he and Dreesen—another comedian, in his late thirties—work like ballplayers once a week in the little clubs in and around L.A. Younger comedians need the exposure, but Letterman and Dreesen are there for the exercise.

"You forget how bad bad comedy is," Letterman says, leaning back. "Guys come up to me all the time and say, 'I wrote this treatment, please read it,' and I almost die. It'll be terrible—the type of stuff I wrote fifteen years ago and thought was really great—and I think, 'Aaaaugh! Maybe I was this bad.'" He struggles to breathe in.

"I know what you mean," says Dreesen, full of impervious good nature. "I've done 41

Tonight Shows. Guys are testing out material on me all the time. Hey, you want to hear a great joke?"

"Yeah," says Letterman, snuffling, sitting up.

"OK," says Dreesen. "A mailman's working his last day on the beat before retiring, and he comes to this house. Well, a woman comes and opens the door wearing a negligee. 'Hi,' she says, 'c'mon in.' So the mailman comes in, and she sits him down and she gives him a beautiful little lunch at the kitchen table. Then she takes him upstairs and shows him to the bed and they kind of go at it, and then they're done and she hands him a dollar. All of a sudden, she hears a noise downstairs and tells the old mailman to hide in the closet, and her husband comes upstairs and says, 'Is anyone here?' 'No,' says the woman, but just then her husband sees the mailman's feet. 'What the hell is this?' he says. 'Well,' his wife says, 'this morning when you left I told you, 'The mailman's retiring, what should I do?' and you said 'Fuck him, give him a buck. The light lunch was my idea.'"

Letterman and Dreesen laugh a long time at this. "That's a great joke," says Letterman.

"A great joke," says Dreesen.

"That joke has everything," says Letterman.

They drive for a while longer while Dreesen talks about traveling around the country and playing dinners in the Midwest and warming up for Dinah Shore. "Have you ever seen a tape of Lenny Bruce performing?" he asks Letterman.

Letterman shakes his head. "No, I haven't," he says and then thinks about it for a second. "Well, maybe bits and pieces."

The night ride is black and smooth until the little lights of Hermosa Beach show up. Dreesen pulls up in front of the Comedy and Magic Club, which has the breezy economy of a Malibu beach house. Inside, about fifty people sit and watch a good young comedian named Rich Hall having a hard night: he has a tape recorder with Groucho glasses talking back to him—he calls the machine Leo Sturges—and it's a funny bit, but he's edgy and off and his heart isn't in it. Hall looks like a scruffy young Buddy Ebsen, and he's full of sodden self-recriminations when he finally gets offstage. "Jesus," he says and stands with his arms folded in a dark corner.

The emcee announces Letterman, and the crowd makes the kind of happy noise a quiz show audience makes when it sees a Honolulu vacation on the prize board. Letterman, a big jock coming home, has a George Brett aspect to him as he looks down, kicks the floor as though it has dirt on it, and looks up. His mouth yanks up into an uneven grin and his funny, froggy-handsome face grimaces, and he shows his soon-to-be-trademarked gapped teeth, runs his hand through his short, boyish bangs, and motions for silence like a scoutmaster.

"Anyone here from Venice?" he says. Ten people yell yes and raise their hands. "Let's tie 'em up and beat the shit out of them!" Letterman says. This drives the crowd to mad laughter.

Letterman paces casually. He knows his own variations; he has played a thousand rooms like this in his young life. He has played Reno and Lake Tahoe and all the little comedy clubs that dot the map of southern California, from which we ladle and draw our new generation of comedians. Letterman is one of those, a young man who left Indiana and radio broadcasting courses at Ball State University and weather forecasting on TV and kids' shows to go to California, where the young comedians go. He had money saved and he thought he was the funniest thing he'd ever met—he could

insult people, rapidly insult people—and he got work writing for Mary Tyler Moore and Jimmie Walker and Bob Newhart and got a good reputation as a comedy intern. He brought his wife with him to California, and then they divorced. Letterman had come west to achieve independent comic's status, though, and was not to be deterred. He set up his own act at Mitzi Shore's Comedy Store in 1975 and was—as most of the good acts in the clubs are—asked to go on The Tonight Show, and he went on The Tonight Show once, twice, three times, and was asked to sit on the couch after his stand-up and talk to Johnny—a great honor and a great help because it displays the merchandise without using up written material—and talked with Johnny and got a call one day from Freddy de Cordova, the producer of the show, and was asked to guest host, which is a specific kind of young comedian's pinnacle, and Letterman was that specific kind of young comedian.

In a moment or two there was a deal from NBC and a new house on the beach at Malibu, and there were articles in various magazines that revealed his stardom, and then an offer from Fred Silverman to get off the stand-up number and sit down in the morning to

host and shore up the network's staggering daytime schedule, revolutionize daytime television, tear the women away from General Hospital and The Jeffersons and High Rollers, which no one—not Jack Paar, not Dick Cavett, not Johnny Carson—had managed to do, although they had all tried at some point early in their careers. Letterman grabbed, agreed, trusted NBC, took the show, and bombed in nineteen weeks. NBC gave him a new contract that paid him twenty thousand dollars a week to do nothing except not work for anyone else without NBC's permission and he took it and here he was in Hermosa Beach making a million dollars a year and facing an audience of fifty-four.

"I like your shoes," a lady in the audience says, pointing up over the stage. "This lady likes my shoes," Letterman says. "So, it's a night well spent." The audience laughs, and he puts one hand in his jean pocket and leans on the microphone stand. "Do you ever get crazy ideas in your head? Just crazy ideas? Like, you're sitting there looking at your dog and you think, if you shave him and oil him up real good, how'll he tan?"

The audience seems to like this idea enough to spur Letterman on to talk about dogs for a while more. The crowd doesn't drop him for a moment—maybe because he shows authority and maybe because he

has authority. In comedy, as in the republic, power without a successor is incomprehensible, and Letterman is widely seen as the successor to the single most powerful position in comedy—for patronage and for influence and for income—the star spot on The Tonight Show. The Tonight Show registers more revenues for NBC than any other piece of its broadcast day or night, and it carries with it the most valuable inheritance in television. In that sense, David Letterman is the George Bush of comedy, a man whose glory depends on succession and for whom the wrong word will ignite a blazing Haig-like public disaster. Just as Johnny Carson idolized Jack Benny, Letterman maintains the same posture toward Carson, and whenever the subject comes up, Letterman has a press-release answer: No one can ever replace Johnny Carson.

!["That Joke Has Everything": David Letterman, Before Late Night]()

Nevertheless. It is an office to be sought. No matter what, the

Tonight host speaks to the nation and has done so since 1962, when President Paar retired to televised safaris and an occasional visit to the Kremlin. Paar's successor, a junior senator from Nebraska, turned out to be the toughest and smartest son of a gun television had ever seen, holding on longer than Paar and his predecessor, former President Steve Allen, put together. Once a year, Carson drums up the kind of jubilee that Victoria arranged for herself only a couple of time in her sixty-four years on the throne and we all watch as Ed Ames hurls the hatchet and kicks off another year of a comedy empire whose social navigations guide us all.

"The point is," Letterman says to his audience, "who

is that woman who sings on Chock Full O'Nuts commercials? Have you ever seen her before? Where did she come from?" Letterman says he loves to slam away at commercials and he does for a while more, and then the audience laughs and yells, "Hey-yo!" and David is off. Driving back to Hollywood in the dark, Dreesen marvels to Letterman at his quickness—how he just managed to take a discussion they'd been having about an L.A. plane hijacking and work it into his act. The hijacker had asked for a million dollars and a getaway helicopter: "A helicopter? A helicopter?" Letterman had asked in his act. "What did he want to do—take it to a shopping mall and spend it at a 7-11?"

"That's great," Dreesen says, "and you just thought it up and twenty minutes later—"

"Yeah, well," says Letterman, "I just talked about it."

"Your recognition is so good," Dreesen says. "I think mine is pretty good when I get up there. Do you know how many

Mervs I've done?" Letterman guesses low.

"Fifty," Dreesen says. "Guess I'll be doing them forever, God willing."

They decide to stop in at a little restaurant in Santa Monica called the Horn, where comics work all night. An excruciatingly bad English-dialect comedian is working and Letterman watches him and holds his stomach as though he were about to have his appendix torn out. After a few minutes of it, he leaves and stands out front where Dreesen talks with Sammy Shore, a short, pleasant-looking older man with Coke-bottle aviators and gray Roman curls, who is something of a legend in L.A. because he and his former wife, Mitzi Shore, founded the Comedy Store.

Shore turns to Letterman and seizes him as though he is speaking to a son. "And as for you," he says. "With all your money and your big new contract—I read about it—you'd better remember you've got responsibilities. You've got to remember who put you where you are and not forget your friends. You've got a lot of power now, David. I hope you know to use it well." Letterman looks mildly alarmed and promises Shore that he

will use it well, even though he's not sure why. It's the first time in his life he has met Sammy Shore.

"Goodnight," he says as Shore starts to try out a new joke on Tom Dreesen, who begins smiling as though he's laying out a runway on which Shore's joke can land. Letterman politely excuses himself and disappears as Shore's joke rises above the sounds of the late night Santa Monica traffic and the British dialect echoing through a bad sound system from inside the Horn ("You know what kind of girl that is," the comic is saying). Shore and Dreesen stand on Wilshire Boulevard laughing at Shore's joke, and suddenly there are two beeps and Letterman's black ceramic BMW shoots down the street past the comics and Dreesen's family car, under the mercury lights and onto the long highway toward Malibu and an early bedtime.

"You know," Johnny Carson said during the monologue on his April 8 show. "I've been thinking if I quit what the line of succession is, and I've been wondering: Would it be Letterman, Bush, Haig—or would it be Letterman, Bush, Tip O'Neill, and then Haig?" Carson doesn't appear to resent Letterman the way he does some of the younger insurgent comedians—Letterman's just moving down the river, coming around, not making the big play. David Letterman may not be our funniest comedian or our best or our most piercing, but he has gotten his education in television and that's what counts.

With talk shows, television takes on a semblance of everydayness—the world is confined within boundaries that are not two-dimensional but that have to do with a compact between the viewer and the performer. The studios are in contact with an entire nation, the talk show regimenting the chaos of reality, creating calm, order. When TV stars, who get crazy and itchy and egomaniacal the way politicians do, can successfully channel their private madness within those boundaries—translating it into the talent and electricity that come across on the screen—they become personalities, sculpted and dependable, voices that can be called on at any moment. It was in that potential that NBC invested when it gave Letterman his own show; it was an investment in a solid-state comedian, good for thirty years or so. By the time NBC put David Letterman on the air in June 1980, its investment was coming along, as Casey Stengel said, slow but fast.

The week before his show went on the air, Letterman's producer, an old friend, retired because of "tremendous creative differences." The show straggled on to its premiere with misplaced spots, lousy skits, dead air, and no structure. Letterman had 90 minutes a day of live television, and writers came and went, imposing bad ideas and untried notions on the audience, sometimes dredging up their old stand-up and performing themselves on the air. Most of the time, Letterman was dominated by his guest, forced to play straight man on his own show.

After two weeks of free-form public-access TV, NBC stepped in and tried to run things: it wanted a variation of the old

Arthur Godfrey Show with a "TV family" of regulars and lots of folksy spots in which Letterman met and conferred with astrologers and vitamin experts ("Have we had B-12 on yet?" a writer yelled from the greenroom one day) and consumer advisers.

They had no producer at all—the head writer, Merrill Markoe (Letterman's girlfriend, who shares his house in Malibu), was running the show—but they finally came up with one: Barry Sands. Sands, a producer on David Frost's and Mike Douglas's shows, redesigned things. Painfully, Letterman got on the phone with station managers around the country and asked them to hang on, not to cancel, to have faith. But of all the networks, NBC was in no position to ask its affiliates to wait for quick-blooming miracles. The show was cut down to 60 minutes, while Philadelphia, Detroit, San Francisco, and Boston replaced Letterman with game shows and situation comedy reruns. The show was left with an 80 percent affiliate coverage (meaning that no matter how high Letterman's per-market ratings were, they'd be cut nationally by a 20 percent function), which made the show a defunct proposition.

Letterman sat on his set, a set as spare as a 1981 Detroit car, with its red carpet and wood paneling and condensed proportions, and watched over the studio. The talk show landscape—the desk, the soft-cloth seats, the opening-and-closing flats, the swivel chair, the cups, and the mic—lives in many Americans' minds as friendly as their childhood classrooms; friendlier. By late September 1980, however, Letterman looked as though he felt the set was treacherous, that it could open up that day and swallow him whole and Orson Bean would be out in a moment to take over. Above him the microphone swiveled like a floating, inquisitive animal. The happy talk show theme plumed up from a small band off to the side (three pieces or four that Letterman billed as the David Letterman Symphony Orchestra), and the big, safari-suited announcer, Bill Wendell, who had a show of his own in jollying up the audience before airtime, announced, "David Letterman."

Grinning gap-toothed in an olive suit, he sat there and pressed his own style on the Carson-mold devices of discussing silly products ("Twirling turtles… there they are, Ladies and Gentlemen—almost

too much entertainment") and fooling around (he got lots and lots of shaving cream all over himself). He read from the big cue cards to introduce his next guest ("Ladies and Gentlemen, you know her from Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman, a fine actress—Louise Lasser!"), and he asked the questions the pre-interviewers had set up for him. "You were once married to Woody Allen, weren't you?" "Yes, yes, I was."

"Was he funny around the house?" Letterman asked.

"I don't know," said Lasser. "Are you funny around the house?" This got a laugh. "Ladies and Gentlemen, a long-time celebrity Louise Lasser!" understood the form somewhat better than David Letterman, a rising young comedian won't you please welcome him. Lasser liked The Interview; Letterman went at it with a ball peen hammer. Someone came around and put more makeup on the Host and the Guest, and when the lights came on after the break, she told her story directly into the television camera, almost oblivious to the talk show star.

"You know," Lasser said to the viewers of 190 NBC affiliates. "It's funny. It was at a time when Woody was being called one of the foremost, you know, one of the

rising young humorists in America, and I thought—well, here I am next to one of the foremost young humorists in America, and I'm bored." This got a huge laugh. Letterman sat by, attending her. "So," she said, "I lean over to him in bed, and he's sleeping, and I say 'Wood,' and I can't get his attention, and I say, 'Wood, say something funny. Make me laugh.' And he says, 'Uhh, leave me alone, huh?' " This got to the audience in a big way and Lasser liked it. Letterman reached for the reins. "We'll be back," he said, trying to detach himself and get a leg up on things in his own television studio. "For more fascinating revelations in a minute."

A half hour later (after a book interview with a dour young apocalyptic economist named Doug Casey, who warned the audience that they would lose all their money and anything they had left unless they did exactly what he told them, and fast), Letterman introduced Edwin Newman.

Newman was sitting in another studio, far from the studio audience. He had gotten a quick lesson in the new age of television when Fred Silverman tried to merge comedy and news in an all-inclusive TV format on Letterman's show. For the first couple of weeks, Newman had sat in the studio with Letterman and read the news and faced applause and laughter. Because Ed Newman was one of the best and most intelligent of all the NBC newsmen, others saw more than a little insult in prodding him to play to an audience. The crowd loved it, but it did no one's dignity any good. Newman moved to an isolation studio.

"Hello, David," he said through a half dozen color monitors, and the picture across the nation shifted to Newman's sweet-and-sour eminence. "Iraq Radio," he read from his booth. "Reports today that the ayatollah is dead." There was a short beat of silence, and then the audience burst into laughter and applause. Letterman sat staring, a little dazed, and then ran his hand over his face.

"Thank you, Ed," he said and was off the air, exhausted.

By the last week in September the word was out on the sidewalk, and Letterman sat behind the talk show desk in Rockefeller Center, the weight of an entire television staff on his bean-pole torso. He sat under the noonday glare of television lights, tossing a pencil into the air and missing it—a talk show acrobat. Around him, the talk show set carried the talk show battleground: big color cameras, heavy lights hanging, dangling power cords, endless monitors. Monitors were everywhere—in the backs of cameras, peering over the set, staring into the audience so that the audience might see what was going on on television.

Letterman was talking to Tom Snyder, who, with thundering inadvertence, had just let it drop that the show had been canceled. "I've had a network show for seven years," Snyder said. "Not many people have had shows that long." "Try seven weeks," Letterman said. "No, I don't mean to say anything about this show," said Snyder. "And I'm sorry it's going off the air." "Ohhh," said the audience.

"Ohhhhh." "No, no, no, no, no," said Letterman, waving his arms.

!["That Joke Has Everything": David Letterman, Before Late Night]()

A day or two later, the official word came. Letterman's show had been canceled, whapped, snuffed, with a three-week stay of execution. He decided that if he had three weeks on the air, he was going to have fun with them. He acted as though he were right at home in his studio, back at WRTV, Indianapolis, and he ran the show. He arranged a "Have

The David Letterman Show in Your Own Home" contest and chose a family in Cresco, Iowa. He flew in a farmer named Floyd Stiles from Collins, Missouri, with his wife, Zola Mae Stiles, and gave him a "Floyd Stiles Day," on which Stiles—who hadn't been to New York before—was treated as a hybrid of Helmut Schmidt and Frank Sinatra. He cut loose with his own jokes until they had a 2:00 a.m. comedy-club edge. He reached for his emergency weapons. Let go, he let go.

By the beginning of October, audiences were packing themselves into the studio to see the self-eulogization of the Letterman show. Letterman had gotten to use his best stuff—and college boys hitched cross-country with petitions to save him. The least mention of the network cancellation brought groans from the studio audience. Some Long Island housewives threatened to block Manhattan traffic until the network relented. A large woman in a bright regal-purple dress and maraschino-red lipstick traveled all the way from Delaware and sat in the front row, a look of massive expectancy in her big eyes. She dragged her poor gray husband—a tiny man, a refugee from Charles Addams in his gray three-piece suit with his thick horn-rimmed glasses, his gray short-brimmed fedora on his lap, and indescribable pain on his face. Each time Letterman said something—anything—the Lady in Purple broke into wild, whooping sounds of joy and laughter. "We've got quite an interesting lineup today," Letterman said. "Whooooop!" said the Lady in Purple, breaking into hysterics, seeking out the camera with the red light, the camera she wanted to have swiveled and pointed at her. Her husband's face writhed into patterns of fury, and he whispered warnings through the side of his mouth, which she ignored as she looked for the camera. "We'll be right back," said David Letterman. "Whooooooooop!" said the lady.

"And now," Letterman said, "we have an authority on the hours when you're not watching this show—from the Harvard Center on Sleep Study, Dr. Quentin Regestein." Dr. Regestein was nervous. He had a small tremble and couldn't remember whether or not it mattered that he mention the title of his book on the air. "Did I pronounce your name correctly? Is it Regestein or

Reegestein?" Letterman asked. Dr. Regestein told him. Somewhere the woman was quivering. "Doctor," Letterman said, "how much sleep would you say the average person needs at night?" "I think," Dr. Regestein was saying, "seven hours is about the right amount of sleep to get." There was a beat of silence.

"Whoooooooop!"

Dr. Regestein smiled, a little shaken. "Seven hours, eh?" Letterman said. "That's more than I usually get." "Well," said Dr. Regestein, "I think it's a good, healthy amount of sleep to get."

"WOOWOOOWHOOOP!" The Lady in Purple was convulsing, shaking at some privately excruciating pleasure/torture, and her husband was desperately trying to rein her in from the side of his mouth, all the while looking straight ahead, furiously. Dr. Regestein gave a pathetic little smile at Letterman. "I seem to be a master at stimulating audiences," he said. "WOOWOOWOOWHOOP!" Her husband's face was a squeezed sponge. This was it for Letterman. He had taken about what he could. He raised one threatening eyebrow in the direction of the trembling, shaking, convulsing woman, but she was infecting the audience around her.

The Lady in Purple, sure that she was on the road to stardom, sat raising her eyebrows, grinning, imploring any eye she could catch to get that red light pointed at her. Whatever disruptive crimes she had committed, she created an air of discomfort and self-recognition among the audience—the girls in low-cut sweaters and cowboy hats, the high school students with signs, the quiz show refugees—and backstage among the guests: the authors in pastel suits, the animal trainers and soap opera stars. Her seismotic shaking and laughter was the rumbling of all of them to be seen, all of

us wanting to get on and be part of it. That was what Letterman was in training to learn to administer if he could just maintain TV order. "Snyder, Carson, Donahue, Cosell," he said one day, going through his Rushmore. "Those are great personalities. They act like actual people would act."

Upstairs at NBC, Barbara Gallagher, the vice president in charge of specials and late-night programming, tried to explain why David wasn't quite ready yet.

"David," she said, "is the only person I can see who can come close to doing a show like Carson. They've got wit. They're both boyish. They're very fast thinkers. I wonder if we'll be looking at TV in twenty years and there David will be with gray hair sitting behind a desk." She smiled at the idea.

"If anyone can grow up to be Johnny Carson," she said, "David can. He's got the best laugh—the cutest, funniest laugh. He's the oldest 33-year-old person on the air. He's learning. He's grown up a lot. Johnny wouldn't think twice about going out and dropping his pants in a sketch. David isn't that sure of himself. Johnny's not afraid to have shaving cream poured on his head," she said. "David isn't that secure yet."

Five months after the last show I went to see Letterman in L.A. Here's how he was: He guest-hosted for Johnny, it went well. He had gotten a million-dollar contract. He had gotten the BMW. His two dogs, Stan and Bob, were healthy. Merrill Markoe was appearing at the Comedy Store on Sunset and taking a script-writing course from Francis Coppola and had almost sworn off television, even though she and Letterman have four sets in their otherwise almost-empty house in Malibu, and she was working on an HBO special called

David Letterman: Looking for Fun.

With their minicam eyes and video sensibilities, Letterman and Markoe, an attractive woman with a Prince Valiant haircut, had been driving around the city for days, picking up names of places that sound funny, tearing through the phone book for living jokes—wax museums (not funny), gag shops (depressing) the Los Angeles River (a cement-guttered stream running through town)—and coming up with sludge. It's a new visual joke, this assiduous tracking down and electronic recording of cultural landmarkings, bringing them back alive so that TV viewers might for the first time realize that they had been looking at jokes all these years without knowing they were funny.

The last time I saw them, they were shooting off in the black ceramic BMW in search of a place in East L.A. called Taco Elvis, sure that it had to be an endlessly kitsch-filled taco joint devoted to the memory of Elvis Presley. Letterman was wearing a Dodgers jacket and driving fast. Markoe was holding a map book.

It took them twenty minutes to get swallowed by the city without a center.

"Where are we?" said Letterman.

"I don't know, you're driving," said Markoe.

"I think, look, it's downtown Los Angeles!" said Letterman.

"It looks just like a city," said Markoe.

"Well, do we turn around?" asked Letterman.

"Well, that's one opinion," said Markoe.

"This would be a dangerous place to find yourself," said Letterman, looking around as they moved deeper into East L.A.

"Well, if you're going to find yourself, I think you'd be better off in East L.A.," said Markoe.

The car had driven into another country with a different language and more empty lots. No Taco Elvis in sight.

"Nope, nope, nope, nope, nope," Letterman said, reading off signs: "Taco Jan's, Taco Jimi's, Taco Juan…"

"I'll bet you anything," Markoe said, "that by the time we get there Taco Elvis has been switched to Taco Ozzie."

Letterman stepped on it. This was the latest installment of the American joke—driving along the end of the continent, looking for a taco stand named for a dead rock star to present to us as The Laugh, a lonely black BMW looking for a funny scar on the side of the road. In the front seat, two frantic intelligences clawed the dry California ground to pan "for something worth watching"—a usable image untouched, unhammered, unclaimed—to bring back and present in a studio and send out along the cables of the continent. The joke found could last its maker and the consumers 10 or 20 or 30 years—a reliable life for which all who create it are grateful—warranting nightly visits on

The Tonight Show or weekly dispatchments on cable, and perhaps, around the year 2030 or so, a postage stamp with Letterman's face on it. The Late-Night King, Old Gap-Tooth, they'd call him, the Man of a Million Midnight Sunrises!—Day-vud Lehdrmn!

Letterman and Markoe peered out the tinted windows of the BMW searching for Taco Elvis, imagining a palace with the statue of the King standing above it and a hundred magazine covers and signed photos inside, and the tacos in the shape of a hound dog and the Love Me Tender Burrito combination. What a laugh on the whole thing that'd be. The numbers passed on Alameda, deeper and deeper into East L.A., and the neighborhoods got poorer and the ground more and more covered with weeds. Alongside the road, on the left side, a little white-stucco hut sat, empty but for a single cook inside, and painted on the front in strong, fiat red paint was just TACO ELVIS, and the joke dissolved: clearly that was Elvis inside running the joint. There was no Viva Las Vegas Enchilada and no Heartbreak Hotel Guacamole. There was just a short-sleeved Elvis behind the counter, and that was the joke, the real joke that you couldn't put on television and consume.

"Let's not go in," said Letterman.

"I don't see any pictures or anything," said Markoe.

"Let's go home," said Letterman.

The black-ceramic BMW turned carefully in the asphalt-patty parking lot at Taco Elvis. The driver reached over to his radio dial and turned until he found what he wanted. Unseen voices filled the car like new passengers, and the driver shot home to Malibu.

Photos via AP

Peter Kaplan was a journalist and one of the most respected editors in the industry. He was the Editor-in-Chief of the New York Observer for fifteen years.

The Stacks is Deadspin's living archive of great journalism, curated by Bronx Banter's Alex Belth. Check out some of our favorites so far. Follow us on Twitter, @DeadspinStacks, or email us at thestacks@deadspin.com.