![The Fault]()

A few weeks ago I spent a morning at the Norman Mailer archives at the University of Texas looking through the research materials for The Executioner's Song, Mailer's 1979 account of the life and death of Utah murderer Gary Gilmore. Around me, students in white gloves turned the pages of leather-bound books so fragile they must have been ancient or holy, perhaps even both.

There was nothing holy about the

Executioner's Song archive. Instead, I paged through the institutional life history—prison psych evaluations, reform school reports, transcriptions of various court appearances—of Gilmore, who, 38 years ago last month, became the first person to be executed in the U.S. after a ten-year moratorium.

Gilmore has the kind of paper trail that you amass if you start getting into trouble as a tween and never really give it up. The experts' conclusions were all over the place: Gary is a sociopath; Gary is not a sociopath. Gary is depressed; Gary's suicide attempts are fakes—he's not depressed, he's just sneaky. Gary has horrible migraines; Gary is a malingerer. Gary smears shit on the walls of his cell, swallows razorblades, sets his mattress on fire, smashes light bulbs and uses the shards to slice his wrists open because he is "a spoiled child" who is "unrealistic in his behavior." "It is significant that he continues his attempt to pass off his improper attitudes and conduct as mental disorder rather than willfully maintained faults of character, which seem to me to be the more likely cause," one prison psychiatrist concluded.

And then in folder 192.6 of the Mailer archive, I found something unexpected: A 20+ page horoscope analysis of Gilmore from astrologer/numerologist Daniel Wexler, along with Wexler's bill for $250. (That's nearly $1000 in 2015 dollars; for comparison purposes, a personalized horoscope book from Susan Miller, the most famous contemporary astrologer, will run you $54.99.) While the horoscope that Wexler drew up never gets mentioned in

The Executioner's Song, it turns out to be a much better description of what made Gary Gilmore tick than anything found in the prison file ("Mars opposition Saturn: Aspect of bad judgment which for years may appear to get away with murder until accumulated flaws topple over the structure of your existence…Venus opposition Saturn: cold or unsympathetic treatment by one or both parents which has tended to warp the emotional nature… Are sensitive and have been hurt much too easily so that you have withdrawn into yourself and give the appearance of being detached and a little hard"). The psych reports, with their insistence on diagnosis and binary crazy/not crazy designations, are useless; the more they insist on coherence, the more they collapse in on themselves. A horoscope, however— no one expects it to make any sense. And then surprisingly, it does.

![The Fault]()

|

|

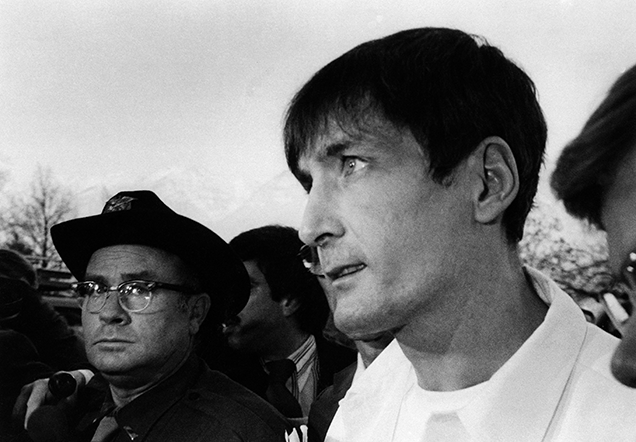

Gilmore on December 3, 1976, on his way to a court hearing to set a date for his execution.

|

Showmanship ran in Gary Gilmore's blood. His paternal grandmother was a circus performer and psychic who performed under the stage name Baby Fay La Foe. She was fond of dropping hints that Gary's real grandfather was a talented but sinister man, a famous man, a man who had died after a blow to the stomach, a man she could never refer to by name, except that his last name was Weiss…It was obvious to everyone that she was talking about Erich Weiss, aka Harry Houdini. (According to Shot in the Heart, the fantastic memoir by Mikal Gilmore, Gary's youngest brother, she almost certainly made the whole thing up.)

Frank Gilmore, Gary's father, was a petty tyrant with a paranoid streak and an impossibly long set of rules. Inevitably, his sons fell short of his standards, and both Gary and his older brother Frank Jr. were subject to weekly belt-whippings. In one scene in

Cremaster 2, Matthew Barney's conceptual treatment of Gary Gilmore's life, Slayer drummer Dave Lombardo sits behind a drum kit, pounding out a frantic, erratic anti-rhythm as thousands of bees swam all over him. It's a perfect evocation of the chaos and random pain that characterized Gary's early years. "My father was the first person I ever wanted to murder," Gary said, shortly before his execution. "If I could have killed him and got away with it, I would have."

Gary grew up to be a leather jacketed reform school kid with a disdain for authority and a strong anti-authoritarian streak. He chugged cough syrup and took hot-wired 57 Chevys for joyrides, abandoning them when they ran out of gas. He robbed pawnshops, grocery stores, and his friends' houses. He went to prison for the first time at age 16, and didn't spend more than two years free for the rest of his life. In prison, he was trouble, too. He spat on guards and flung his food on the floor when it wasn't to his taste. He displayed a visceral, undiscriminating hatred for anyone in uniform.

Despite his rage and selfishness, though, there was something about Gary that made people want to give him another chance. The flip side of his cruelty was his sensitivity; he was a man who'd been deeply wounded by the world, and it showed. Despite his long history of criminal behavior, Gary could seem almost innocent at times. He was a talented artist, and he produced dozens of sketches of his favorite subject: sad-eyed children, "round faces with a bewildered, inviolable innocence," Mikal Gilmore writes. But then again, he drew a lot of porno scenes, too.

When his prison term for armed robbery was up, his aunt and uncle—deeply moral Mormons, with a strong commitment to forgiveness and mercy—decided he could live with them in Provo, Utah. And so in April of 1976, despite the misgivings of some prison officials, Gary was released into his relatives' care. It was the biggest second chance of his life.

![The Fault]()

|

|

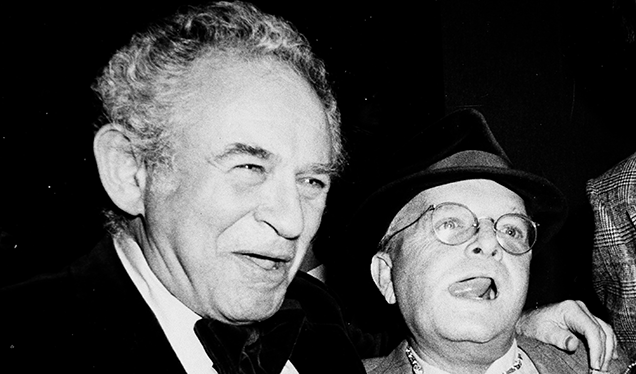

Mailer and his wife, Adele, sitting together in court in December 1960. Adele declined to press charges when Mailer stabbed her twice with a penknife. |

Norman Mailer was never really a person I expected to feel kinship with. I first knew him from various TV clips of his fights with other writers, back when that was the sort of thing that made prime time. I disliked him right away. He had the posture of a bully. He'd lean across the table, chest puffed, or sprawl back in his chair, transmitting contempt with his entire body. He looked like a man who would stab his wife and try to run for mayor anyway. No one I knew read him. I assumed his fame was just one of those mistakes that got made in the mid-20th century, back when people were more apt to confuse bravado and a certain thrusty kind of prose for genius. Fuck that guy.

When I first read

The Executioner's Song a few years ago, though, I ran into a problem: it really is, as Joan Didion wrote in her 1979 New York Times review, "an absolutely astonishing book." Some of that is because Gilmore appealed to Mailer's taste for prison poets and self-reflective con men. He was a blue-eyed car thief in scuffed boots, a mythical dirtbag antihero who roamed the highways and cheap motels of the American West. It's no surprise that Mailer was good at getting drunk, job-quitting, prison-hating Gary on paper.

What I didn't expect is that the book's most potent voices, the ones that stick in your head long after Gary's bluster has faded, are those of women: Gary's defeated mother, his deeply moral aunt, and Nicole, his damaged, hopeful girlfriend. All of Mailer's evident admiration for Gilmore's outlaw romance is balanced against the pain and disappointment of these women.

![The Fault]()

|

|

Gilmore, shouting "I love her more than life itself!" following a court hearing. He was speaking about Nicole Barrett. |

During the nine brief months between Gary's release from prison and his execution, he fought with his family, his bosses, and random strangers. When he didn't have enough money to buy beer, he stole it. Freedom had other benefits, though: Not long after his release, Gary met Nicole Barrett, a thrice-divorced 19-year-old single mother. They fell quickly and deeply in love, and Gary moved in with her. But while Nicole was devoted to Gary, she was also afraid of him. After he hit her one too many times, she left him.

One hot night in July, Gary convinced Nicole's little sister, April, to go for a ride. He had, as usual, been drinking. At about 10:30 PM, he stopped in front of a Sinclair gas station and told April to wait in the car. He walked inside and held the clerk, Max Jensen up at gunpoint. After Jensen emptied the cash register, Gilmore ordered him to lie down on the floor in the gas station bathroom. "This one is for me," he said, shooting Jensen in the head once. "And this is for Nicole," he said with the second shot. Then Gilmore walked back to the car and took April to see

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. The next day, Gilmore drove to the City Center motel, where he again demanded money—this time from motel manager Ben Bushnell— and then killed the man who'd given it to him.

Gary didn't have much of a plan for the money he'd stolen, or for getting away with the murders. He was captured within a day, after his aunt turned him in. Believing that he'd murdered the two men as a way of stopping himself from killing her, which she found impossibly romantic, Nicole rekindled her relationship with Gary. They exchanged hundreds of letters during the months he spent on Death Row.

![The Fault]()

|

|

Mailer and Truman Capote at the New York Discotheque in 1978.

|

I learned later that despite his no-bullshit reputation, Mailer apparently had a

"deep respect" for astrology. You can find his natal chart online, too. He and Gilmore have a shared Saturn problem, as it turns out:

"Moon square Saturn- a hectic emotional life…you may be the despair of yourself and your friends. Through excessive dependence you hurt your parents, thru erratic action your sweethearts… If the horoscope has a negative bent, then this aspect may lead to depression of spirits, dejection, and a sense of frustration…"

I don't know why it brought me so much comfort to find out that Mailer was into astrology— maybe it's simply because it makes him seem a little bit silly, and it's always fun to see a pompous man made a little bit ridiculous. But then again, I read my horoscope, too. I appreciate astrology as a kind of metaphor for the powerful or seemingly random forces that shape us — the brains we're born with, all the sneaky or lucky tricks of fate that alter the courses of our lives.

Astrologically speaking, I have more in common with Mailer than I do with Gilmore. Our suns square neptune ("artist's soul"); our suns sextile mars (very competitive). We have the same Saturn/Libra intimacy issues. An accident of stardust doesn't make me and Norman Mailer best friends, of course. But maybe we're not as incompatible as I had thought.

Your chart, with its houses and conjunctions and trines, doesn't insist that you possess a solid, consistent self, but instead presumes that you're a jumble of competing characteristics that sometimes work against each other. You can be a murderer and a gifted artist, a sweet boyfriend and an abuser, a bad man with bright spots.

![The Fault]()

|

|

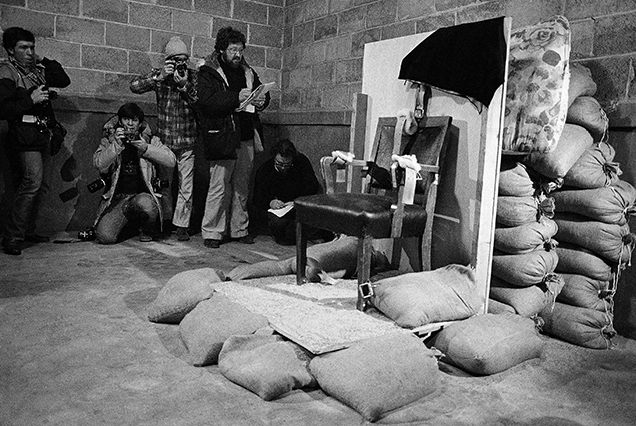

Photographers shoot the chair where Gilmore was executed. |

Gary Gilmore's trial took two days. His state appointed attorneys didn't have much to work with; it was obvious that Gary had committed the murders, and that he hadn't been insane or otherwise out of control. On October 7, 1976, the jury unanimously recommended the death penalty.

If things had proceeded normally, Gary would've faced at least a decade on Death Row as he worked through his appeals. There was even a good chance he'd never actually be put to death: The United States hadn't executed anyone in over a decade, thanks to the Supreme Court's temporary suspension of capital punishment. While the death penalty had been reinstated earlier in 1976, there was still a pervasive discomfort at the idea of starting up the execution machine all over again. Death penalty opponents were hard at work on cases that they hoped might do away with capital punishment in the United States for good.

But Gary Gilmore wasn't interested in appeals, or more meetings with lawyers, or the incremental progress of justice. After being sentenced to death, he fired his lawyers, gave up his appeals, and asked to be executed as soon as possible. This caught everyone off guard: Prisoners were supposed to fight their state-sponsored executions, not embrace them. Death penalty opponents adopted Gilmore as a cause celebre, scrambling for legal work-arounds to delay his execution, while Gilmore, furious and ready to die, called them idiots at every opportunity. (Gilmore's insistence on his own execution likely impeded efforts to fight the death penalty on a national level, and hastened the execution of some of his fellow prisoners. This never seemed to bother him very much.)

Gilmore's self-propelled journey toward death brought with it an unexpected consequence: fame. For the first three decades of his life, he was a lowlife, a nobody. Suddenly, his face was emblazoned on t-shirts and he had a starring role in the five-o-clock news. "The last months of [Gilmore's] life were expensively, exhaustively covered, covered in teams, covered in packs, covered with checkbooks and covered with tricks," Didion wrote in her

Executioner's Song review. "It seemed one of those lives in which the narrative would yield no further meaning." During his three months on Death Row, he received stacks of fan mail; his hero, Johnny Cash, called him up on the prison telephone. Gary Gilmore, convicted killer, was famous.

![The Fault]()

|

|

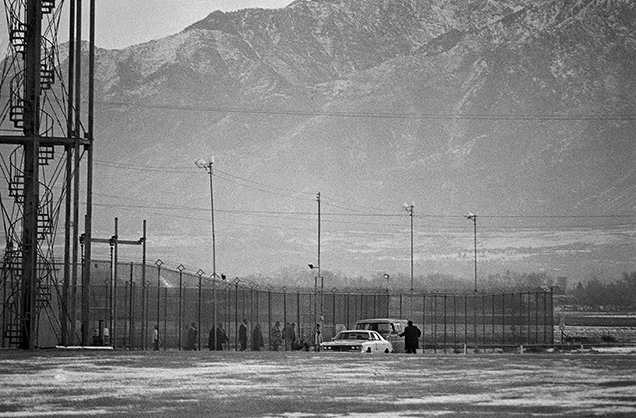

Gilmore and officials before dawn on January 17, walking to cars for the ride to the execution site. |

Though he was articulate about many other things, Gary could never fully explain why he shot those two men. Neither murder was a crime of passion, or a bid for power; he wasn't driven by rage or hatred or psychosis or delusions. He was a little drunk, a little high—but not

that drunk, not that high. Both men had already given him the money he was ostensibly after. There was no sense behind it, except maybe for the fact that both of his victims were Mormon men, young fathers, working men— like some sort of parallel universe versions of Gary with most of the damage removed.

In his memoir, Mikal Gilmore wonders if Gary was cursed from the moment of conception. Later, he walks this statement back a bit, placing his brother in the category of people "who had the possibility of murder jammed deep inside their hearts at an early age." Of course, not every possibility comes true, just as every horoscope is merely a prediction, not a decree of fate. There were four Gilmore brothers who all grew up with the same family weather; only one of them ever killed anyone.

Everyone who writes about Gilmore faces down this

why, this big blank. Mikal Gilmore calls it the "empty Utah night"; Didion, the flashiest girl at the party, writes about "that vast emptiness at the center of the Western experience, a nihilism antithetical not only to literature but to most other forms of human endeavor, a dread so close to zero that human voices fadeout, trail off, like skywriting."

Funny, isn't it. Where you might expect to find the language of the ever-deepening abyss, all these writers think instead of an emptiness that extends upward, and the vast infinity of the western sky—that old stand-in for God, or fate, or whatever else we call things too big to fit inside us.

![The Fault]()

|

|

Gilmore t-shirts for sale in Amherst, Mass., three weeks after his execution. |

I'm thinking about Gary Gilmore a lot these days because I've been trying to work my way into the head of a different murderer, a guy in prison in Texas. Like Gilmore, there's no question that he committed the crime he's in prison for. This isn't some

Serial did-he-do-it investigation where I'm trying to suss out the truth and find justice for a possibly innocent person. My guy's acknowledgement of his own guilt makes things simpler in some ways, but more complicated in others. "Did he do it?" presumes a yes-or-no response. "Why did he do it?" is, on some level, unanswerable—which is to say, a question you can attempt to answer forever, in as many pages as you want, and never feel fully satisfied. (No wonder The Executioner's Song weighs in at 1136 pages, a smidge heftier than even Infinite Jest.)

If your mind works a certain way, it's easy to get deep into this stuff, so deep that when you're home for the holidays and your parents' neighbors or your middle school friends ask you what you're working on, you forget yourself and answer honestly: "Oh, this murder thing!" It's a guaranteed way to get people to give you weird looks. There's something unseemly, vaguely ugly, about voluntarily spending your time in such dark places. I know that when my middle school friend says "Now how did you come to be interested in that?", there's a question underneath her question. Or maybe it's a warning. Something like:

Just what are you looking for? And what are you hoping to find?

But maybe that's the wrong question. People look

for clues or proof or evidence of psychopathology. There's a place for this kind of evaluative mission; it's the job of jurors, doctors, and certain kinds of journalists. Looking at has a worse reputation—it's the purview of rubberneckers and voyeurs, gawkers, people who get off on witnessing other people's messiness. But what about looking just to look, without any secret diagnostic motive, without attempting a resolution or cure? I like to think that's how the constellations were named: A long time ago, someone saw something in an alignment of stars, and it meant something to him, and he gave it a name.

We still live under that same blank sky. We still spend long winter nights telling each other stories, making patterns out of infinity, looking for new angles on that

something wrong. Better, I suppose, to look too long than to not look at all.

![The Fault]()

|

| Attendants carry Gilmore's body into the Utah State Medical Center following his execution.

|

In Europe, where millions were marched to their executions only seven decades ago, only Belarus retains the death penalty. The European Union "regards abolition as essential for the protection of human dignity, as well as for the progressive development of human rights"; in 2011, it banned the export of drugs used in lethal injections. Faced with a dwindling supply of sodium thiopental, the only component of the standard lethal-injection cocktail no longer in wide enough use for easy purchase, several states have begun initiating procedures to

bring back the firing squad. Bills in Utah and Wyoming are currently working their way through those states' legislatures.

It's likely that when these states start shooting people again, it won't merit the weeks of front-page coverage that Gary Gilmore's execution did. The stars are differently aligned. Support for the death penalty has slowly declined in the U.S. since its peak in the 1990s, but a clear majority of Americans still believes in capital punishment for murder. Faced with evidence that capital punishment is applied arbitrarily or unjustly, it's easy to explain away our Death Row inmates as psychopaths. Certainly some of them are—but calling someone a psychopath can also be a way to say "I don't want to think about this person anymore." Willful ignorance is precarious, too.

"No I ain't drunk or loaded," Gary wrote Nicole from Death Row, in one of a hundred-plus letters they exchanged in the weeks before his execution. "this is just me writing this letter that lacks beauty—just me Gary Gilmore thief and murderer. Crazy Gary. Who will one day have a dream that he was a guy named GARY in 20th century America and that there was something very wrong."

At dawn on January 17, 1977, Gary Gilmore was walked to an abandoned building behind the prison and strapped to a chair. When asked to make an official last statement, he said "Let's do it." A decade later an advertising executive named Dan Wieden was casting about for ideas for a campaign for Nike sneakers. "Some things you don't look at while you're doing them. Otherwise you can't do them properly," he later said. He landed on Gilmore's final moments."I liked the 'do it' part of it... None of us really paid that much attention."The most famous advertising slogan of the 20th century was born. "Like a lot of things in life, sometimes it's the most inadvertent things, that you don't really see. People started reading things into it much more than sport."

But the actual last words that Gilmore spoke were to a priest. They have none of the fuck-it bravado of a shoe company tag line.

There will always be a father, Gary said. Then he was shot to death by five upstanding Utah citizens.

Rachel Monroe has previously written for Oxford American, the New York Times, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and The Awl.

[Top illustration by Jim Cooke]

Gawker Review of Books is a new hub for book, art, and film coverage. Find us on Twitter.